In 2017 during Hurricane Irma, a tree branch hit a transformer and knocked out the main air conditioning system for a nursing home in Hollywood, Florida. There were portable air conditioners onsite, but they proved insufficient as indoor temperatures rose to a sweltering 100°F over the course of a three-day outage. Ultimately, 12 residents tragically lost their lives to the extreme heat.

Sadly, the conditions that precipitated this disaster are all too common, and are poised to become more so. Both the number of heatwaves in American cities and their duration have been increasing for decades due to climate change. In New York City alone, extreme heat claims 120 lives annually, and 80% of those deaths occur in people’s own homes.

To examine this issue, I co-authored a study in the journal Building and Environment with Drs. Kaiyu Sun and Tianzhen Hong, researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Amidst the variety of options buildings have to improve thermal survivability during heat waves, power outages, and associated events, could energy efficiency play a role in keeping occupants safe? According to our results, the answer is yes.

It is well established that energy efficient buildings can save customers money, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve health and well-being, and make occupants more productive. Yet the extent to which efficiency impacts our ability to adapt to, withstand, and rapidly recover from heat-related disasters – i.e., to become more resilient – has been less well studied. And many that do look at the issue largely consider only hypothetical buildings.

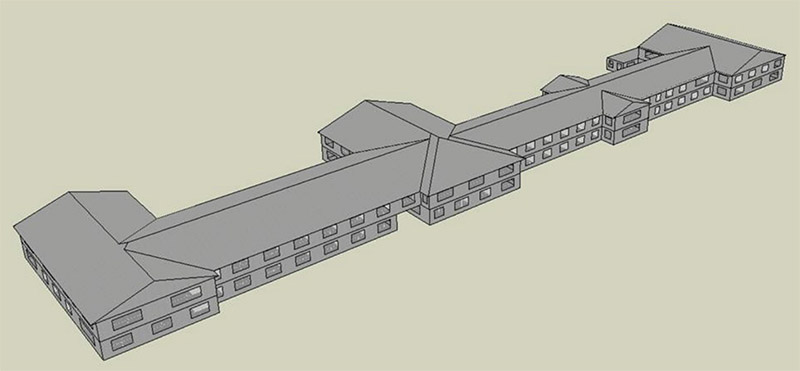

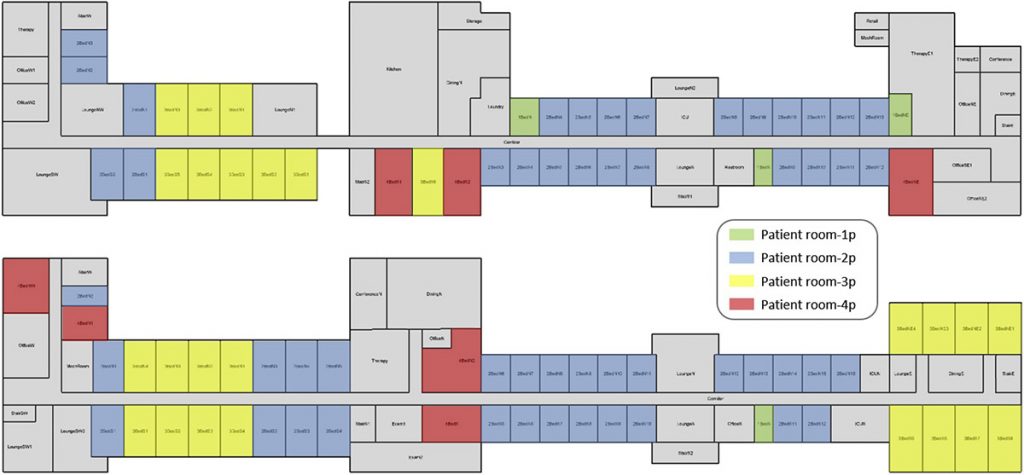

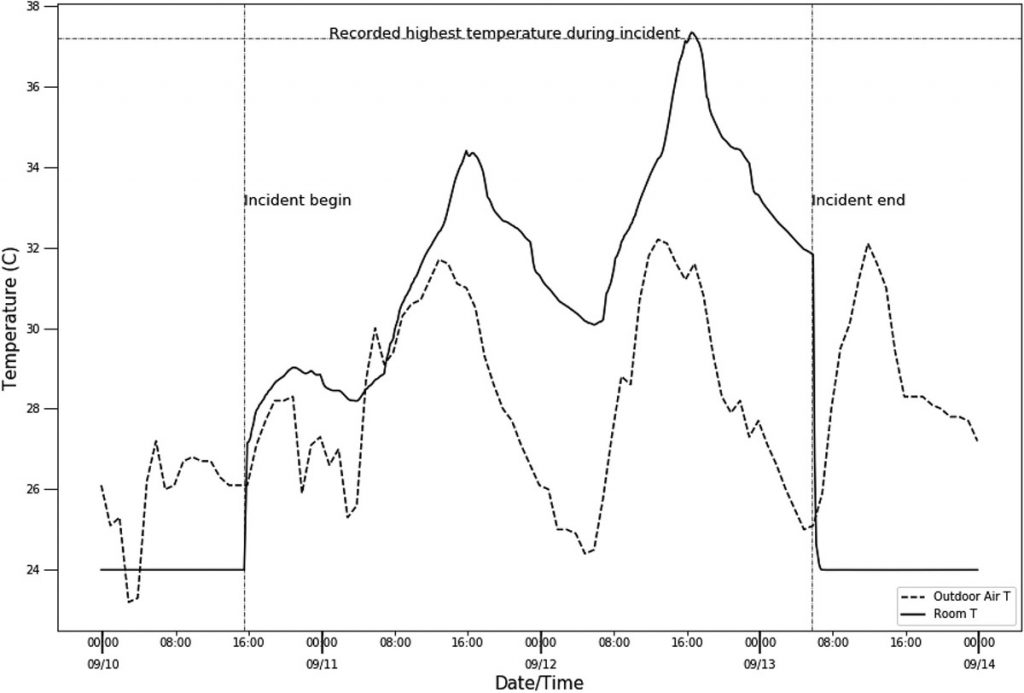

However, in the case of the Hollywood nursing home, we had a real-world example of a failed building. Weather data during the outage were available, as was a measured indoor temperature. Dr. Sun gathered the actual building data (e.g., floor plans, building components, renovation history) through publicly available records and recreated the nursing home in EnergyPlus modeling software.

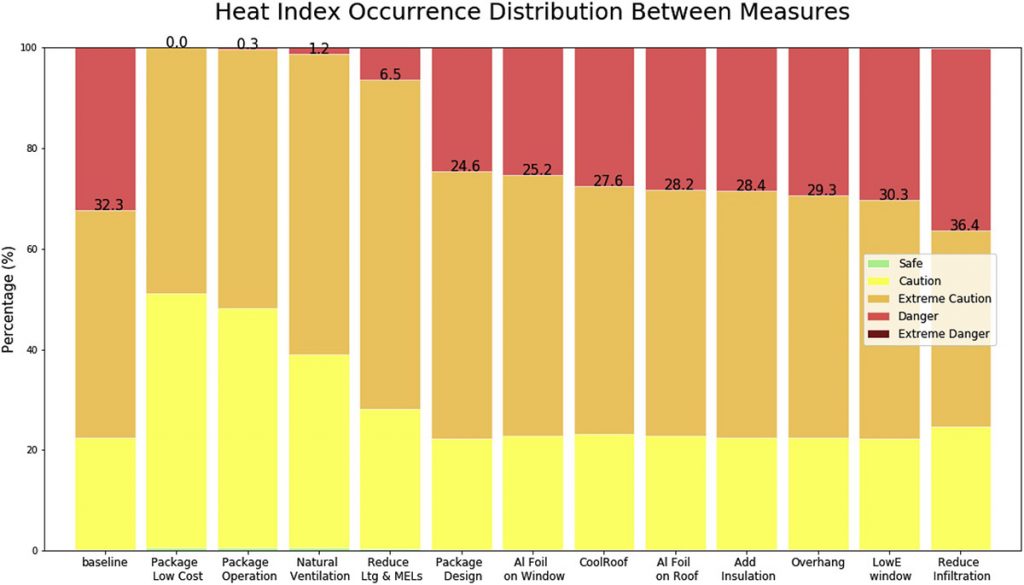

We introduced a variety of energy conservation measures like higher insulation, shielding windows and the roof with aluminum foil, applying a cool roof coating, reducing air infiltration, adding exterior shading, turning off miscellaneous electrical loads (e.g., lighting), and adding natural ventilation.

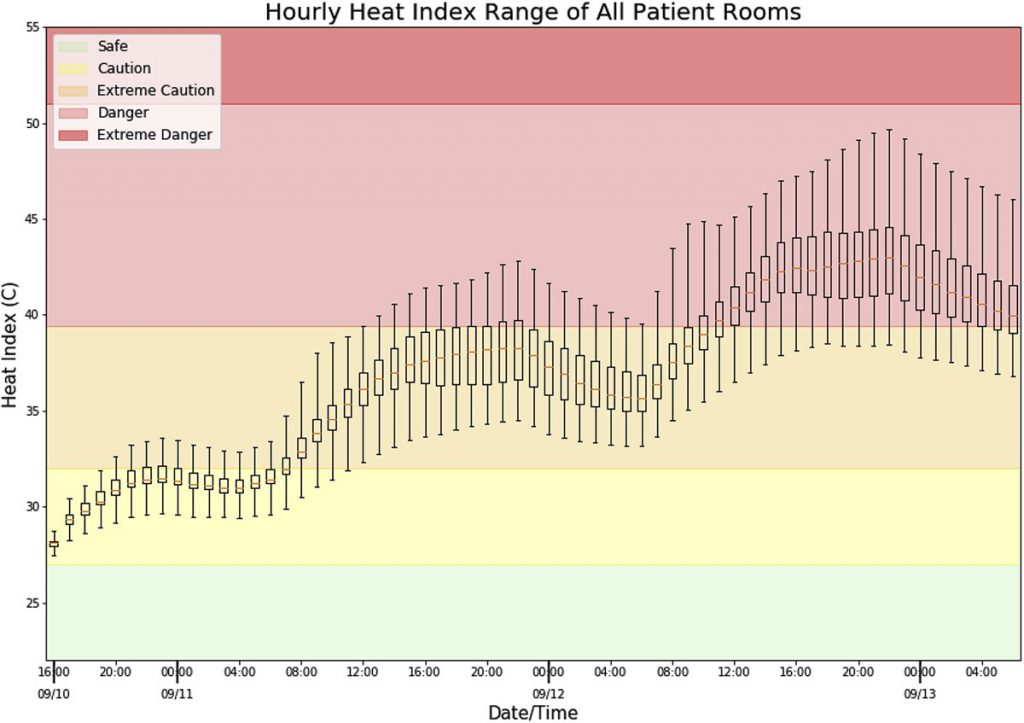

We discovered that most measures would have reduced the indoor heat index, a metric that accounts for both temperature and humidity, thereby enhancing thermal survivability. In addition, we found the most effective measure – simply opening the windows – would have cost nothing at all. However, some efficiency improvements were less beneficial than others, and one actually would have had a negative impact on resilience. Moreover, if we placed the same nursing home in a heat wave in a different city, the set of most effective measures would have changed.

I’ll quote the paper itself:

Our analysis generated three high-level takeaways. First, energy efficiency is not uniformly beneficial for resilience, as different efficiency characteristics convey different resilience impacts. In particular, we found that reduced air infiltration—a staple of modern energy efficiency practices—actually made it more difficult for the nursing home to expel excess heat when indoor air temperature was higher than it was outdoors. And it would have, on its own, increased the heat index beyond the status quo. Second, the effectiveness of specific energy efficiency measures varied as a function of circumstance. By transplanting the Florida nursing home to Chicago and San Francisco during real heatwaves, we found that the value of individual measures varied as a function of multiple parameters, including climate zone, outdoor temperature, length of air conditioning outage, insolation, and local building codes. Third, the most effective efficiency measures were also the least expensive to implement. This encouraging result indicates that low-to no-cost measures could potentially be deployed in buildings in near-real time to enhance passive survivability by allowing residents to shelter-in-place.

I should caution that while many of these efficiency measures reduced the danger for occupants, they did not on their own make the building safe. Some additional form of energy storage was needed for that, but even 8 hours of chilled water cooling capacity would have been sufficient to keep most room-hours within the “safe” zone for the majority of the outage.

I encourage those interested in expanding the value of energy efficiency, and those eager for new pathways to enhance resilience to refer to this study. It not only demonstrates a real connection between energy efficient buildings and thermal survivability, but also that this nexus is nuanced and ripe for further exploration.